This week’s Torah commentary from Hebrew Seminary has been sponsored by Alan Gotthelf in memory of his mother, Chaya Ruchel bat Yosef and Esther Malka, who passed away hours before Kol Nidre in 2012.

To sustain Hebrew Seminary’s work of bringing the words of the Torah to life, please consider sponsoring an upcoming Torah commentary through your gift of any amount.

* * *

A Prayer for the Distracted at Prayer: Commentary on Yom Kippur 5785

By Rabbi Jonah Rank, Rosh Yeshivah of Hebrew Seminary

Every once in a while, I try to draft in my imagination my ideal workday schedule:

5:45 AM: Wake up

6:00 AM: Wake up kids

6:10 AM: Feed kids breakfast

6:35 AM: Drive kids to bus stop

6:45 AM: Deliver kids to bus stop

6:55 AM: Return home

7:00 AM: Pray Shacharit (morning service)

7:30 AM: Exercise

8:00 AM: Study Torah

9:00 AM: Work

1:00 PM: Lunch Break

1:20 PM: Pray Minchah (afternoon service)

1:30 PM: Work

3:50 PM: Drive back to bus stop

4:00 PM: Pick up kids at bus stop

4:10 PM: Return home

4:15 PM: Back to work

5:45 PM: Make and serve dinner

7:00 PM: Volunteer for an important cause

9:00 PM: Study Torah

10:00 PM: Pray Arvit (evening service)

10:15 PM: Clean

10:45 PM: Go to sleep

As it turns out, I have never once experienced such a day in my lifetime. One incidental or another inevitably arises. An appliance breaks. A meeting runs over. A bus is late. Somebody in the house wakes up sick (or sometimes several of us do). Or I might even have to run an errand.

Exercise all too regularly gets axed from my to-dos, dinner runs late, the Torah study and the sleep are shorter than I’d wish, and prayer might be rushed because of an endless stream of last-minute to-dos.

How can any human possibly fit into their day all of the things that must happen?

For some among us, life may be centered by paid work, and, for others, life’s axis may revolve around friends, family, and other loved ones. Still for others, volunteering one’s time and talents may take up the better part of their day. Whatever may be of utmost concern to our own souls can consume us for our entire lives if we allow it.

With so many distractions in our lives, what time could we possibly have for self-care, healing, or spiritual concerns? For many of us, our obligations to others prevent us from recognizing our own needs.

On their webpage “The Science of Adult Capabilities,” the psychologists behind Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child list focusing, planning, awareness, and self-control among the “core capabilities” a human needs in order to possess strong executive functioning skills. When I think about that unachievable ideal schedule, I worry how I, in my adulthood, might be graded here. Fortunately though, the same psychologists list “flexibility” as another core competency, instilling in me the hope that my ability to go with the (unpredictable) flow may yet be my own saving grace.

In contrast to Harvard’s understanding of how a successful human might organize themselves, the Jewish tradition has made sacred time and again the divinity of a disorganized religion. Modern biblical scholars often enjoy claiming that the Torah’s inclusion of contradicting narratives or descriptions suggests that our Torah is not one focused document; rather, the Torah constitutes a scattered anthology of religious thinkers recording holy but inconsistent stories. Such academics thus like to note that, whereas Genesis 7:12 reports of the weather surrounding Noah’s ark, “וַיְהִ֥י הַגֶּ֖שֶׁם עַל־הָאָ֑רֶץ אַרְבָּעִ֣ים י֔וֹם וְאַרְבָּעִ֖ים לָֽיְלָה׃” (“The rain was upon the earth for forty days and forty nights”), Genesis 8:5 recalls a much longer flood; “וְהַמַּ֗יִם הָיוּ֙ הָל֣וֹךְ וְחָס֔וֹר עַ֖ד הַחֹ֣דֶשׁ הָֽעֲשִׂירִ֑י” (“the waters were continuing to diminish through the tenth month”). The Torah is not defined by its clear throughline; rather, the Torah is shaped by the weaving of disjointed thoughts into a cloth made richer by the contrasts in its design.

The rabbis loved and devoted their efforts to finding meaning in the Hebrew Bible’s disjunctions. In a very short ancient Jewish text called Baraita DeRabbi Yishma’el (ברייתא דרבי ישמעאל), rabbinic tradition attributes to the 1st-2nd century C.E. sage Rabbi Yishma’el in the Land of Israel thirteen rules for deriving practical laws from the Torah; approximately half of these hermeneutic principles focus on how to make sense of seeming contradictions in biblical texts. Moreover, the rabbis whose hands most heavily edited the Babylonian Talmud in the second half of the 1st millennium C.E. opted not to create a series of books that would make Judaism easy. Instead, the Babylonian Talmud offers far more challenges to than acceptances of any proposed solutions to any queries the sages ever raised. Large swaths of the Talmud, therefore, read less like a philosopher zeroing in on a particular subject and more like a passionate argument about how any or even every single detail of what we think is true is false. The mind of the Talmud is unquiet and unfocused.

In most synagogues today, Yom Kippur presents the longest service of the entire year, often beginning earlier and ending later than any other morning service. During such a long stretch of prayers, the mind may rightfully wander. In fact, one myth that comes to explain the origin of the piyyut (prayer-”poem”) that begins with the words “היום תאמצנו” (HaYom Te’ammetzenu, “Today, Grant Us Courage”) presumes that many of the worshipers missed out on the majority of the prayer experience. The piyyut, in most printed versions in Ashkenazic communities, reads as follows:

.הַיּוֹם תְּאַמְּצֵנוּ. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תְּבָרְכֵנוּ. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תְּגַדְּלֵנוּ. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תִּדְרְשֵׁנוּ לְטוֹבָה. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תִּשְׁמַע שַׁוְעָתֵנוּ. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תְּקַבֵּל בְּרַחֲמִים וּבְרָצוֹן אֶת תְּפִלָּתֵנוּ. אָמֵן

.הַיּוֹם תִּתְמְכֵנוּ בִּימִין צִדְקֶךָ. אָמֵן

Today, grant us courage. Amen.

Today, bless us. Amen.

Today, raise us. Amen.

Today, seek us for good. Amen.

Today, hear our cry. Amen.

Today, receive our prayer mercifully and willingly. Amen.

Today, support us with the righteousness of Your right hand. Amen.

Reciting this short piyyut guides the worshiper to ask God directly for support. The prayer is hardly novel; elsewhere in the traditional text of the Amidah prayer in the morning, the worshiper has already commanded God, “ברכנו” (barekhenu, “Bless us”), and has already called God “ישועתנו ועזרתנו” (yeshu’atenu ve’ezratenu, “our salvation and our help”). Every sentiment in this piyyut draws upon earlier declarations in the Yom Kippur prayer service. So who really needs this prayer?

In 1923 Vilna (now in Lithuania), the Widow and Brothers Romm Press released Siddur UMachzor Kol Bo Nusach Sefard (סדור ומחזור כל בו נוסח ספרד), a multi-volume collection of prayerbooks for the whole year, guided by largely anonymous teachings lumped together under the name Kol Bo (כל בו, literally meaning “Everything Inside It”). In explaining the origins of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu,” the Kol Bo commentary reads:

היום תברכנו ברכה לבעלי תשובה… ואנו כלנו חוזרים בתשובה ולכן נקבע ברכה זו בסוף התפלה וכן אלהינו ואלהי אבותינו ברכנו וכו׳ כאדם שנפטר מרבו וכן מאביו ואמר ברכני רבי או ברכני אבי… וכן אנו נוהגים בשבתות ומודעים שבסוף התפלה הולכים הנערים להמברכים כמו להרב או אצל אביהם כלומר התפללו לפני הקב״ה ראוים אנו לברכה אך בימי החול אין נוהגין כן שאין העם פנוים לבא לביה״כ

“HaYom Tevarekhenu[,” the second line of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu,”] is a blessing for those practicing teshuvah (תשובה, “repentance”), but we all return [to God] through teshuvah. Therefore this blessing was affixed for us at the end of the Amidah. So too, [the inclusion near the end of the Amidah of] “אלהינו ואלהי אבותינו ברכנו” (“Our God and God of our ancestors, bless us”) [in the introduction to the Priestly Blessing] etc. is akin to a person who departs from their master or from their father and has said, “Bless me, my rabbi,” or “Bless me, my father…” So too, we practice on Shabbat and holidays that, at the end of the Amidah, the young ones walk over to those reciting blessings, such as the rabbi or their parent, as if to say, “Pray before the Holy Blessed One that we may be deserving of a blessing.” However on weekdays, we do not follow this practice, for the [people of] the nation are not available to go [then] to the synagogue. (Vol. I: LeRosh HaShanah, p. 304.)

We do not know exactly how many years children habitually approached their superiors to demand a blessing at the end of services. In present-day Brooklyn, Rabbi Alexander Eliezer Knopfler claimed to have found that the German scholar Rabbi Wolf Heidenheim (1757-1832) reported this very ritual in his day. (See Knopfler’s first responsum in Ran Yosef Chayyim Mas’ud ben Mosheh Avichatzira [רן יוסף חיים מסעוד בן משה אביחצירא] [ed.], Kovetz Gilyonot MeReYaCh Nicho’ach [קובץ גליונות מרי״ח ניחוח], no. 368 [Beha’alotekha 5777], p. 38.) This prayer though, allegedly designed for those who, despite being in synagogue for hours upon hours, somehow totally missed that they had already petitioned God to bless them, was composed centuries earlier. The 12th century Machzor Vitry, composed by a student of the great French Jewish commentator Rashi (1028-1105), mentions “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” as it rattles off in shorthand a listing of prayers that should conclude Musaf, traditionally the final service of Rosh HaShanah’s morning. (See, for example, the edition by Aryeh Goldschmidt, vol. 3, p. 749.)

While contemporary practice includes this prayer typically only in the Musaf services of Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, service leaders used to bestow this prayer upon those who apparently lacked the affirmation of blessing at other times of the year. The 13th-14th century French Rabbi Aharon HaKohen of Lunel wrote in his Orchot Chayyim (ארחות חיים, literally “Paths of Life“) that certain communities would recite “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” at the end of services on the dramatic seventh and final day of Sukkot, when Jews, having taken hold of their lulav and etrog for the last time of the season, have dramatically beaten their willows. (See, for example, the edition by Rabbi Shalom Y. Klein, p. 106.) Among approximately a dozen versions of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” that can be found in medieval manuscripts, the Taylor-Schechter collection of Hebraica housed at Cambridge University includes a (long) version of this prayer adjacent to the seasonal prayer for Geshem (גשם, “Rain”) recited on Shemini Atzeret, one day after Sukkot has ended. Though these folios are written in Hebrew scripts that are no longer in use, these texts, cataloged as T-S H15.154 (1r) and T-S H15.154 (1v), scanned onto the internet, are now accessible to more readers than ever before.

Image of T-S H15.154 (1r), with a long version of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu.”

Image of T-S H15.154 (1r), with a long version of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu.”

Image of the adjacent T-S H15.154 (1v), with a prayer for Geshem on Shemini Atzeret.

Image of the adjacent T-S H15.154 (1v), with a prayer for Geshem on Shemini Atzeret.

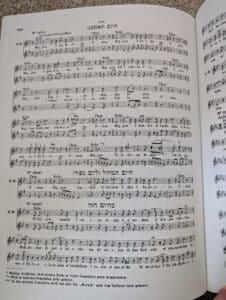

Formally a litany, a poetic work that returns to the same word or phrase over and over, “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” packs its punch as a prayer very concisely. The repetition of the word “HaYom” (“היום,” “Today”) in every line heightens the urgency of the moment, and the short phrases (usually just one word long) squeezed between “HaYom” and the congregational response of Amen easily invite musical arrangements. Because of how easily and metrically most of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” flows, Jewish musicians have composed for “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” melodies that range from bouncy and energetic to beautiful and elegant. In 1871 Nuremberg, when Abraham Baer (1834-1894) published Baal T’fillah, the first ever transcription of sheet music for every prayer throughout the entire Jewish year, he highlighted “HaYom Te’ammetzenu.” Though he prescribed that most prayers of the year should be recited according to a simple chant by a solo cantor, Baer offered two arrangements for this prayer, each inviting choral participation for those who, in one way or another, missed out on the earlier blessings of the day.

Image of Baer’s parallel sheet music for two versions of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu.”

Image of Baer’s parallel sheet music for two versions of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu.”

For me, there is something inspiring and radically inclusive about a religion that does not come to a full stop after teaching “מצוות צריכות כוונה” (mitzvot tzerikhot kavvanah, “[the performance of] mitzvot requires intentionality,” as per the Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 13a). Rather, Judaism canonizes a spiritual practice for those among us who lose our focus or even miss the bigger picture. “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” is not a prayer for those who already got their fill of blessings by however many hours they had already sat in synagogue. Instead, “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” succinctly summarizes what we hope God will grant us after we tried our darnedest to perform as our best selves before the Divine. In this regard, “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” identifies us as either those who prayed all day but are not sure if the prayers worked at all or those of us who came far too late to services and now need a brief synopsis.

By stressing the seriousness of this very day and this very occasion, “HaYom Te’ammetzenu,” reminds us that every minute of our lives count. Our daily to-do lists may be daunting no matter who we are. If we are passionate about nearly anything in the world, we will always end our days with more work to be done, accepting that, by the time we go to bed, there is a good chance we will have not gotten around yet to one important task or another. But “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” allows us to be gentle on ourselves, for God can ease those whose minds and souls are cluttered by distractions or even the anxiety of feeling insufficient or excluded in this world. The rhythm of “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” embraces us, compelling us to affirm our belief in both a God and a community who, in the simplest terms, will grant us the courage to move forward when we are too unfocused to locate the path ahead. “HaYom Te’ammetzenu” permits us to accept the warmth of community where, though neither our prayers may be immediately answered nor our concerns quickly dispelled, our prayers will nonetheless be affirmed.

On any day when we all gather, no matter where our hearts reside, we can still reach out for one last blessing.

* * *

Every week, Hebrew Seminary publishes words of contemporary Torah commentary, linking the words of our past to the values of our here and now. Committed to making Jewish life accessible, Hebrew Seminary’s weekly Torah commentary allows readers around the world to nourish their neshamot (“souls”) with words of Torah composed by Hebrew Seminary’s students, faculty, graduates, and friends.