This week’s Torah commentary, written by Hebrew Seminary Rosh Yeshivah Rabbi Jonah Rank and first published in 2022, has been sponsored by Judith Pottier.

* * *

As I write these words, 15 days after the mass shooting at the Highland Park 4th of July Celebration 2022, our news outlets continue to share updates of victims whose conditions have worsened since the terrible incident. This senseless act of gun violence impacted our own community at Hebrew Seminary; members of our faculty, our friends, and our families had themselves been present at what would catastrophically become a crime scene.

Living in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, claiming today an average of over 400 Americans dying daily in the last two weeks alone, we in the United States remain threatened by the endemic of gun violence. Indeed, the Gun Violence Archive records that guns have been responsible for of over 200 Americans’ deaths on average each day of 2022. Just as we have all learned ways to prevent the transmission of COVID-19—masking, distancing, and the like—we must learn what it will take to stop the spread of gun violence.

Remembering that we humans, like all other organisms that walk this earth, are merely animals—anthropology demonstrates that aggression is a trait human beings share with many other species, including many of our primate relatives among them. Yet, humans are blessed with free will, the capacity to live off of far more than fight-or-flight reflexes alone. The Divine force who endowed humans with the God-like trait of living an examined life bespeaks the same Heavenly authority that told the Israelites, “I have offered you life or death, blessings or curses; choose life so that you and your offspring may live” (Deuteronomy 30:19). Evolution alone cannot account for our whole being as moral creatures. Nature and the ordinary are too low a bar for an organism who strives for a higher ethic. In Jewish life, we strive to experience the supernatural; in our secular lives, we aim for the extraordinary.

It is therefore a fortuitous sign of the times when the very moral consciousness of modern Jews leads us to a place of shame when we read the opening of this week’s Torah portion, Pinechas. Though our ancestors were instructed to love the stranger (which the Babylonian Talmud, Bava Metzi’a 59b, recounts the Torah instructing us as such dozens of times)—we are stunned by Aaron’s grandson Pinechas, who fatally wounds the Israelite Zimri and the Midianite Kozbi for their multifaith cohabitation (as per Numbers 25:16–18). What is even more repugnant to our moral sensibilities is that the God of the Israelites appears to reward Pinechas for his belligerence. The Divine tells Moses to inform Pinechas that the latter will be blessed with God’s “covenant of peace, and that he and his offspring… will possess the covenant of eternal priesthood” (Numbers 25:12–13).

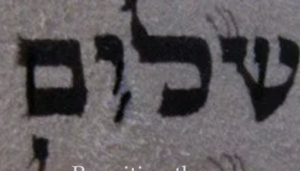

Our generation is not the first to be taken aback by the thought that God bequeathed a covenant of peace to a spear-wielding homicidal zealot. According to the Babylonian Talmud, Rav Nachman argued some 17 centuries ago that the word שָׁלוֹם (shalom, “peace”) should be spelled with its letter ו (Vav) קְטִיעָה (keti’ah, “sliced”) here (Kiddushin 66b). In contemporary practice, the scribe Mordechai Pinchas offers his own attempt at presenting this segmented Vav in this place of strange peace:

Image of the Hebrew word shalom as appearing in a Torah scroll with a break in the letter Vav, accessed at https://www.sofer.co.uk/broken-vav on July 19, 2022.

The mismatch of this hateful act in a text that preaches love led to centuries of esoteric and evasive understandings of this stricken Vav. For example, Rabbi Ya’akov ben Asher (in 13th–14th century Germany and Spain) suggested that the Vav is broken in pieces to allude to a Vav that traversed several time periods. Following a teaching appearing in the late 1st-millennium rabbinic anthology Pirkey DeRabbi Eli’ezer 47:8 equating Pinechas with the (much later) prophet Elijah—Rabbi Ya’akov claimed that a multigenerational Vav was even once on loan to our ancestor Jacob (Ya’akov in Hebrew). Jacob’s Hebrew name is only occasionally spelled with a Vav in the Hebrew Bible. This letter but was supposed to be collected in the Messianic era by Elijah (whose Hebrew name is almost always spelled with a Vav in the Hebrew Bible). (See Ba’al HaTurim, on Numbers 25:12.)

But there is a much simpler explanation for the rupture of this Vav. Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin—the once-rabbi of Lutsk, Ukraine, who died in 1966 in Israel—wrote in his extensive Torah commentary Oznayim LaTorah on Numbers 25:12:

וא״ו קטיעא. מכיון שהשלום הזה נרכש ע״י שפיכת דם… אין הקב״ה שמח במפלתם של רשעים. וצערו של הקב״ה ע״ז נתבטא בוא״ו קטיעא של מלת שלום, שהוא שמו של הקב״ה.

The Vav is sliced. This is because this peace was earned by way of spilling blood…. The Holy Blessed One does not rejoice in the downfall of the wicked. Thus, the pain of the Holy Blessed One is thereby expressed through the sliced Vav of the word Shalom—which is the name of the Holy Blessed One.

Indeed, the very name of holiness, God, has been slashed by the fatal blows that Pinechas dealt to an Israelite who, in linking himself to a Moabite woman and her religion, committed an idolatrous act. Polytheism may be heretical for a Jewish boy, but civility today would urge us to understand that a religious belief or practice that affects nobody outside the practitioner presents no case for capital punishment. On the other hand, Pinechas may have believed that he fought for, and achieved, peace, and he certainly saw himself as doing what was right in the eyes of the Lord. Still, in fact and in writing, God could not attach God’s own name to Pinechas’ fundamentalism without first mutilating the name of Peace. No matter any attempt to justify—no weapon is a tool of peace.

We are just a few months away from the end of the year 5782 on the Jewish calendar, and, if we do nothing, we may be sadly slated to witness more violence before Rosh HaShanah. But, to honor the memories of those who were slain without cause on July 4 in Highland Park—and throughout the United States nearly every day—we can and must demand a world with greater peace. We need a world where laws, conduct, and discourse prevent the next false justification for violence against the innocent. The offense never renders a society safer.

To honor the lives lost and the wounded from gun violence, now is the time to talk about reducing—and ending—violence. Now is the time to partner with our communities, to ask our civic leaders to step in, to be good neighbors, and to model extraordinary kindness in the public sphere among strangers.

Now is the time to act so that future generations may merit to write the story of their lives, with the word shalom, with an unbroken Vav.

* * *